Iran’s Execution Surge; silence should not be an option

17 Dec 14

Note: This column is an English translation of an article published in Le Temps on December 16, 2014.

Iran’s Execution Surge; silence should not be an option

By Mahmood Amiry-Moghaddam and Raphaël Chenuil-Hazan

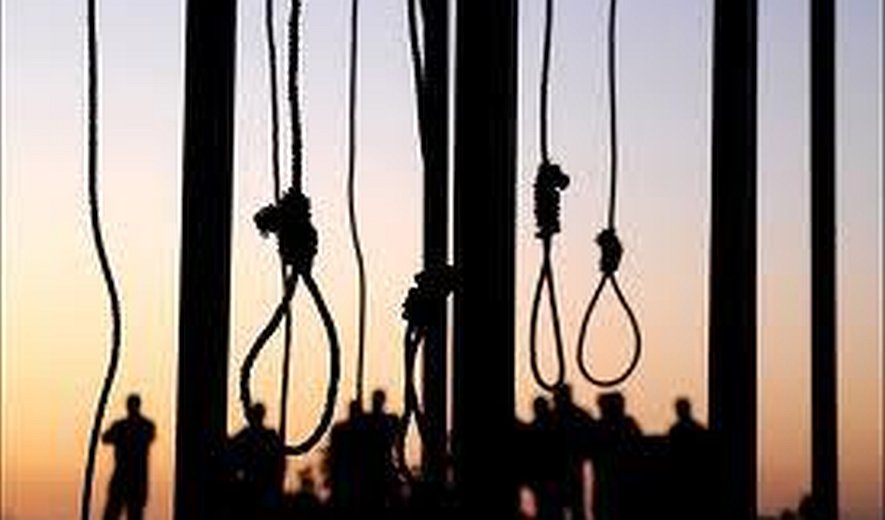

On 18 November, the United Nations General Assembly passed its annual resolution raising concern for human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran, including the country’s surge in executions. Today Iran is the world’s leading executioner per capita. Its death penalty practice particularly callous and lawless often marked by execution of juvenile offenders, public hangings, and gross due process violations.

Not surprisingly, the UN resolution received strong support in amongst Francophone nations, where 62 about of 77 states have abolished the death penalty by law or in practice. The Central African Republic, Haiti, Cameroon, France and others voted in favor the resolution.

Yet, several countries failed to join the international consensus, including the Senegal, Rawanda, Lao, Tunisia and Gabon, who actually abstained from voting. This silence is disappointing. And, sadly, Comoros voted against the resolution despite voting for it last year.

Behind closed doors some diplomats explain that the election of Hassan Rouhani to President of the Islamic Republic and improved political relations with Iran makes them less inclined to vote on such resolutions. Yet all reports indicate that the human rights situation, especially with regards to the use of the death penalty, has deteriorated.

Last month’s execution of Reyhaneh Jabbari should have alerted everyone to this deterioration. Despite repeated and clear international calls for a stay of execution, authorities executed Jabbari, a young woman who was convicted of murdering a man attempting to sexually assault her. The UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights quickly condemned this execution, raising due process deficiencies. Her conviction was allegedly based on confessions made under duress. The court also apparently failed to consider any evidence of the attempted sexual assault.

Unfortunately, Jabbari’s case is not unique. Since June 2013, when Mr. Rouhani assumed office, on average two people have been executed every day in Iran. That is more than 870 executions in Mr. Rouhani’s first year in office, the highest annual figure in 20 years in Iran. Moreover, these death sentences commonly steam from on tortured confessions and trials conducted without the presences of a lawyer for the accused.

Though Iran has pledged to respect at least the minimum standards regarding the death penalty, the majority of executions are for offenses that fall outside the category of “most serious” crimes, needed to justify the sentence. According to the UN about 63% of the executions in Iran documented since 2011, were for drug-related crimes, which do not meet this international criterion. Over the last year, in a few cases it even appears individuals have even been executed for peaceful political activism.

Iran has also not yet eliminated the death penalty for juvenile offenders, and has so far executed at least 13 juveniles in 2014. In April, Iran executed four juvenile offenders in four days, one of which was Ebrahim Hajati, hanged for a murder he committed when he was 16 years old.

It is a paradox that relations between Iran and the international community are improving while the rate of executions in Iran is spiraling out of control. If this is the case, should Iranian authorities not be expected to be more accountable towards international concerns, not less? Instead, when the UN Secretary-General recently expressed dismay at the country’s execution policies the head of Iran’s Judiciary Sadegh Larijani, responded, “Who is Mr. Secretary-General to tell us we should stop executions?”

Today, it is more important than ever to focus on human rights and put the death penalty at top of the agenda in any dialogue with Iran. The UN must be the driving voice for reforms that lead to a decrease and finally an abolition of the death penalty.

International human rights demands enjoy strong support among the Iranian people. Mr. Rouhani was elected on a platform of human rights pledges. Public sentiment in Iran is increasingly turning against the use of the death penalty, especially executions in public, drug-related sentences, and juvenile executions. This shift isn’t limited to the human rights defenders and the civil society either. Several religious clerics have raised voice against certain aspects of the death penalty. It is time, which have ceased executing their own citizens should ask, ‘do Iranians deserve less rights?’

In late December the UNGA will reconvene for another vote that formally adopts the resolution on human rights in Iran. Francophone nations will have another chance to remind ordinary Iranians and their government that the right to life is an international concern by voting “yes.”

Mahmood Amiry-Moghaddam, Executive Director of Iran Human Right (IHR) and member of the Steering Committee of the World Coalition against the Death Penalty

Raphaël Chenuil-Hazan, Executive Director of Ensemble contre la peine de mort (ECPM) and Vice-President of the World Coalition of the Death Penalty

Iran Human Right (IHR) and Ensemble contre la peine de mort (ECPM) are members of the international network Impact Iran (impactiran.org)

Not surprisingly, the UN resolution received strong support in amongst Francophone nations, where 62 about of 77 states have abolished the death penalty by law or in practice. The Central African Republic, Haiti, Cameroon, France and others voted in favor the resolution.

Yet, several countries failed to join the international consensus, including the Senegal, Rawanda, Lao, Tunisia and Gabon, who actually abstained from voting. This silence is disappointing. And, sadly, Comoros voted against the resolution despite voting for it last year.

Behind closed doors some diplomats explain that the election of Hassan Rouhani to President of the Islamic Republic and improved political relations with Iran makes them less inclined to vote on such resolutions. Yet all reports indicate that the human rights situation, especially with regards to the use of the death penalty, has deteriorated.

Last month’s execution of Reyhaneh Jabbari should have alerted everyone to this deterioration. Despite repeated and clear international calls for a stay of execution, authorities executed Jabbari, a young woman who was convicted of murdering a man attempting to sexually assault her. The UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights quickly condemned this execution, raising due process deficiencies. Her conviction was allegedly based on confessions made under duress. The court also apparently failed to consider any evidence of the attempted sexual assault.

Unfortunately, Jabbari’s case is not unique. Since June 2013, when Mr. Rouhani assumed office, on average two people have been executed every day in Iran. That is more than 870 executions in Mr. Rouhani’s first year in office, the highest annual figure in 20 years in Iran. Moreover, these death sentences commonly steam from on tortured confessions and trials conducted without the presences of a lawyer for the accused.

Though Iran has pledged to respect at least the minimum standards regarding the death penalty, the majority of executions are for offenses that fall outside the category of “most serious” crimes, needed to justify the sentence. According to the UN about 63% of the executions in Iran documented since 2011, were for drug-related crimes, which do not meet this international criterion. Over the last year, in a few cases it even appears individuals have even been executed for peaceful political activism.

Iran has also not yet eliminated the death penalty for juvenile offenders, and has so far executed at least 13 juveniles in 2014. In April, Iran executed four juvenile offenders in four days, one of which was Ebrahim Hajati, hanged for a murder he committed when he was 16 years old.

It is a paradox that relations between Iran and the international community are improving while the rate of executions in Iran is spiraling out of control. If this is the case, should Iranian authorities not be expected to be more accountable towards international concerns, not less? Instead, when the UN Secretary-General recently expressed dismay at the country’s execution policies the head of Iran’s Judiciary Sadegh Larijani, responded, “Who is Mr. Secretary-General to tell us we should stop executions?”

Today, it is more important than ever to focus on human rights and put the death penalty at top of the agenda in any dialogue with Iran. The UN must be the driving voice for reforms that lead to a decrease and finally an abolition of the death penalty.

International human rights demands enjoy strong support among the Iranian people. Mr. Rouhani was elected on a platform of human rights pledges. Public sentiment in Iran is increasingly turning against the use of the death penalty, especially executions in public, drug-related sentences, and juvenile executions. This shift isn’t limited to the human rights defenders and the civil society either. Several religious clerics have raised voice against certain aspects of the death penalty. It is time, which have ceased executing their own citizens should ask, ‘do Iranians deserve less rights?’

In late December the UNGA will reconvene for another vote that formally adopts the resolution on human rights in Iran. Francophone nations will have another chance to remind ordinary Iranians and their government that the right to life is an international concern by voting “yes.”

Mahmood Amiry-Moghaddam, Executive Director of Iran Human Right (IHR) and member of the Steering Committee of the World Coalition against the Death Penalty

Raphaël Chenuil-Hazan, Executive Director of Ensemble contre la peine de mort (ECPM) and Vice-President of the World Coalition of the Death Penalty

Iran Human Right (IHR) and Ensemble contre la peine de mort (ECPM) are members of the international network Impact Iran (impactiran.org)