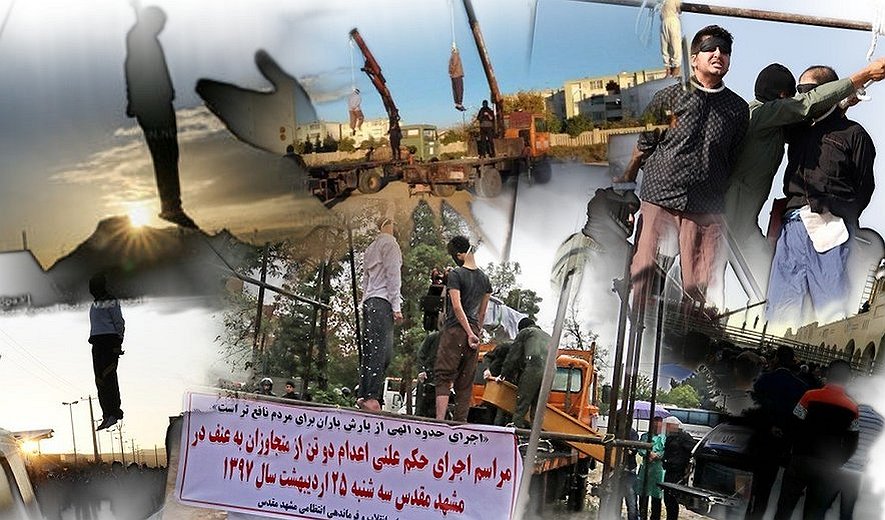

Iran Report: Execution of Women, Juveniles, Ethnic Minorities and Foreigners in 2018

Iran Human Rights (IHR); March 26, 2019: A part of the 11th Annual Report on the Death Penalty in Iran, by IHR, deals with the execution of women, juveniles, ethnic minorities and foreign citizens in the country.

Juvenile executions: Trends and legislative reforms

In February 2018, noting a surge in the number of juvenile offenders being executed in Iran, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein urged Iran “to abide by international law and immediately halt all executions of people sentenced to death for crimes committed when they were under eighteen.” He said that “No other State comes even remotely close to the total number of juveniles who have been executed in Iran over the past couple of decades.”[1]

Iran remains one of the few countries sentencing juveniles to death and it executes more juvenile offenders than any other country in the world. In violation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which Iran has ratified, the Iranian authorities executed at least six juvenile offenders in 2018, one juvenile execution more than in 2017. According to IHR’s reports, at least 61 juvenile offenders have been executed between 2008 and 2018 in Iran. Amnesty International recently reported the execution of 85 juvenile offenders between 2005 and 2018.[2] According to the same report, at least 80 juvenile offenders are on death row in Iranian prisons.

However, the actual number is significantly higher as there is no information about juvenile offenders in many Iranian prisons.

The international pressure on Iran’s execution of juvenile offenders increased during the 2000-decade. As a consequence of the criticism from the international community and the internal civil society, Iran made changes regarding juvenile offenders in the Islamic Penal Code (IPC). However, these changes have not led to a decrease in the number of juvenile executions. The new Islamic Penal Code (IPC) adopted in 2013 explicitly defines the “age of criminal responsibility” for children as the age of maturity under shari’a law, meaning that girls over nine lunar years of age and boys over fifteen lunar years of age are eligible for execution if convicted of “crimes against God” (such as apostasy) or “retribution crimes” (such as “intentional murder”).[3] Article 91 of the IPC says that juvenile offenders under the age of 18 who commit hodoud or qisas offences may not be sentenced to death if the judge determines the offender lacked “adequate mental maturity and the ability to reason” based on forensic evidence.[4] This article allows judges to assess a juvenile offender’s mental maturity at the time of the offence and, potentially, to impose an alternative punishment to the death penalty on the basis of the outcome. In 2014, Iran’s Supreme Court confirmed that all juvenile offenders on death row could apply for a retrial.

However, Article 91 is vaguely worded and inconsistently and arbitrarily applied. In the period of 2016-2018, IHR has identified 17 identified five cases where the death sentences of juvenile offenders were converted based on Article 91. In the same period, at least 16 juvenile offenders were executed according to IHR reports, and several are in danger of execution. It seems that Article 91 has not led to a decrease in the number of juvenile executions. The Iranian authorities must change the law, unconditionally removing all death sentences for all offences committed under 18 years of age.

The UN Special Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Iran states in his report regarding Article 91: “Building upon the amendment, the Special Rapporteur calls upon the Government to introduce a further amendment, which affirming the lack of mental development of a juvenile, absolutely prohibits the execution of persons who were under the age of 18 years of age at the time of their offence.”[5]

Some facts about juvenile executions in 2018:

6 were executed (one more than in 2017)

2 girls were among those executed- both child brides charged with murdering their husbands

5 juveniles had their death sentences converted based on Article 91

Juvenile offenders executed in 2018

Amir Hossein Pourjafar

Amir Hossein Pourjafar, who was charged with rape and murder when he was less than 16 years old, was executed at Rajai Shahr Prison on January 4, 2018. Amir Hossein Pourjafar’s lawyer had previously told an official medium, “Amir Hossein was born on December 17, 1999; so technically he wasn’t even 16 at the time of the murder, i.e. on April 11, 2016”. The Criminal Court of Tehran issued the death sentence of Amir Hossain Pourjafar based on an assessment by the forensics which stated that the defendant was mentally mature at the time of the crime and he was aware of the nature of the crime and the consequences of his action.[6]

Amir Hossein Pourjafar, who was charged with rape and murder when he was less than 16 years old, was executed at Rajai Shahr Prison on January 4, 2018. Amir Hossein Pourjafar’s lawyer had previously told an official medium, “Amir Hossein was born on December 17, 1999; so technically he wasn’t even 16 at the time of the murder, i.e. on April 11, 2016”. The Criminal Court of Tehran issued the death sentence of Amir Hossain Pourjafar based on an assessment by the forensics which stated that the defendant was mentally mature at the time of the crime and he was aware of the nature of the crime and the consequences of his action.[6]

Ali Kazemi

Ali Kazemi, a juvenile offender who committed a murder at age 15, was hanged on January 30, 2018, at Bushehr Central Prison.[7] The murder was reportedly committed seven years ago and Ali Kazemi was 22 at the time of the execution. Ali Kazemi was hanged in Bushehr Central Prison (Southern Iran).

Ali Kazemi, a juvenile offender who committed a murder at age 15, was hanged on January 30, 2018, at Bushehr Central Prison.[7] The murder was reportedly committed seven years ago and Ali Kazemi was 22 at the time of the execution. Ali Kazemi was hanged in Bushehr Central Prison (Southern Iran).

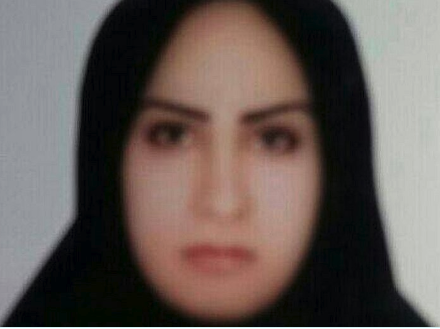

Mahboubeh Mofidi

Mahboubeh Mofidi, nicknamed Newly Bride by Iranian media at the time of her arrest, was accused of killing her husband at the age of 17.[8] Mahbubeh Mofidi was charged with poisoning her husband with the help of her brother-in-law (victim’s brother) on December 17, 2013, a month after their marriage ceremony. The juvenile offender was arrested a few months after the murder when the result of forensic toxicology was issued. Prosecutor of Noshahr had said in an interview with the official media: “The woman was arrested, and she confessed to the murder with the help of one of her relatives. She said that she fell in love with her brother-in-law after her marriage and they finally decided to get married”. The Prosecutor continued, “The victim’s brother carried out the plan and provided aluminum phosphide in capsules, and his wife made him take the pills which resulted in his death.”

Mahboubeh Mofidi, nicknamed Newly Bride by Iranian media at the time of her arrest, was accused of killing her husband at the age of 17.[8] Mahbubeh Mofidi was charged with poisoning her husband with the help of her brother-in-law (victim’s brother) on December 17, 2013, a month after their marriage ceremony. The juvenile offender was arrested a few months after the murder when the result of forensic toxicology was issued. Prosecutor of Noshahr had said in an interview with the official media: “The woman was arrested, and she confessed to the murder with the help of one of her relatives. She said that she fell in love with her brother-in-law after her marriage and they finally decided to get married”. The Prosecutor continued, “The victim’s brother carried out the plan and provided aluminum phosphide in capsules, and his wife made him take the pills which resulted in his death.”

One of Mahboubeh Mofidi’s relatives on condition of anonymity told IHR that “Mahbubeh was the victim of fratricide. She was deceived by her husband and married him, but his evil brother tricked her after the marriage so that he could kill his brother. Mahbubeh didn’t know what exactly was inside the capsules and trusted her brother-in-law.”[9]

Abolfazl Chazani Sharahi

Abolfazl Chazani Sharahi, a juvenile offender charged with murder at the age of 15, was executed on June 27 at Qom Central Prison in Iran.[10] Abolfazl Chazani Sharahi, son of Asghar, was born on January 19, 1999, and he was only 15 at the time of the crime. Abolfazl was examined by a forensic physician at the request of his public defender on July 20, 2014. According to the report, “The defendant, 15 years and five months old, committed murder in the winter last year and he is mentally mature and understands the nature of his action (murder).”An Iranian newspaper confirmed his execution 43 days after the sentence was carried out.[11] The United Nations High Commissioner for Human rights had strongly condemned this execution [12]

Abolfazl Chazani Sharahi, a juvenile offender charged with murder at the age of 15, was executed on June 27 at Qom Central Prison in Iran.[10] Abolfazl Chazani Sharahi, son of Asghar, was born on January 19, 1999, and he was only 15 at the time of the crime. Abolfazl was examined by a forensic physician at the request of his public defender on July 20, 2014. According to the report, “The defendant, 15 years and five months old, committed murder in the winter last year and he is mentally mature and understands the nature of his action (murder).”An Iranian newspaper confirmed his execution 43 days after the sentence was carried out.[11] The United Nations High Commissioner for Human rights had strongly condemned this execution [12]

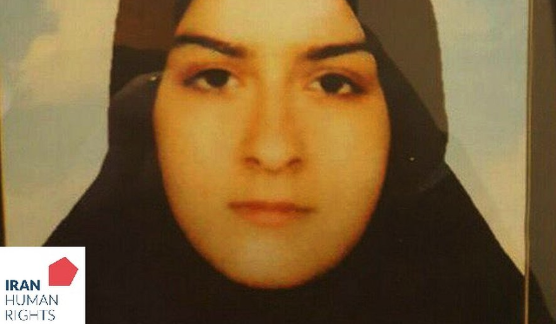

Zeinab Sekanvand

Zeinab was 17 years old when she was arrested in 2012. Charged for the murdering of her husband. She was executed on October 2, 2018, at Urmia prison.[13] The Iranian media outlets have not reported the execution so far. Zeinab was born on June 22, 1994, and was arrested on March 1, 2012, for the murder of her husband. She was sentenced to death by branch 2 of Urmia's criminal court. Her death sentence was confirmed by branch 8 of Iran's Supreme Court. Zeinab was reportedly married to a man when she was 15 years old and, according to sources close to her, she was abused by her husband. IHR has obtained parts of the text of Zeinab's court verdict. According to the document, Zeinab was physically abused by her husband and she filed a complaint with Iranian authorities. However, Iranian authorities reportedly did not follow up on her complaint. Zeinab Sekaanvand spent the first two years of her imprisonment in Khoy Prison (West Azerbaijan province, northwestern Iran). However, when she was sentenced to death, she was transferred to the women's ward of Urmia Central Prison. She was scheduled to be executed in October 2016 but her death sentence was postponed.

Zeinab was 17 years old when she was arrested in 2012. Charged for the murdering of her husband. She was executed on October 2, 2018, at Urmia prison.[13] The Iranian media outlets have not reported the execution so far. Zeinab was born on June 22, 1994, and was arrested on March 1, 2012, for the murder of her husband. She was sentenced to death by branch 2 of Urmia's criminal court. Her death sentence was confirmed by branch 8 of Iran's Supreme Court. Zeinab was reportedly married to a man when she was 15 years old and, according to sources close to her, she was abused by her husband. IHR has obtained parts of the text of Zeinab's court verdict. According to the document, Zeinab was physically abused by her husband and she filed a complaint with Iranian authorities. However, Iranian authorities reportedly did not follow up on her complaint. Zeinab Sekaanvand spent the first two years of her imprisonment in Khoy Prison (West Azerbaijan province, northwestern Iran). However, when she was sentenced to death, she was transferred to the women's ward of Urmia Central Prison. She was scheduled to be executed in October 2016 but her death sentence was postponed.

Women

According to reports gathered by IHR, at least 5 women were executed in 2019 in Iran. Only two of the executions were announced by official sources.

All of the five women executed in 2018 had been sentenced to death on murder charges.

The surname of one of the women has not been revealed, despite the fact that the execution was officially announced.

Some facts about the women executed in 2018:

5 executions but only two announced by the authorities

2 of them were juvenile offenders

All were sentenced to death for murder charges

At least 3 were charged with murdering their husbands- 2 were child brides

Ethnic minorities

The 2018 and all the previous reports indicate that the ethnic minorities, especially Kurds and Baluchis are over-represented in the death penalty statistics. An exact differentiation of the executions based on ethnicity is not possible for several reasons. Usually, people who are executed in the ethnic regions come from these regions. However, the executions of people who belong to different ethnic groups are not implemented exclusively in their respective regions. Moreover, information about those executed doesn't always include their ethnicity. However, a look at the number of people in different ethnic regions shows that the number of executions in areas such as West Azerbaijan (where most of the Kurdish prisoners are held) and Baluchestan is higher than the average (See geographical distribution and number of executions per capita).

In addition, prisons in the ethnic regions of Iran have a high percentage of unannounced or secret executions

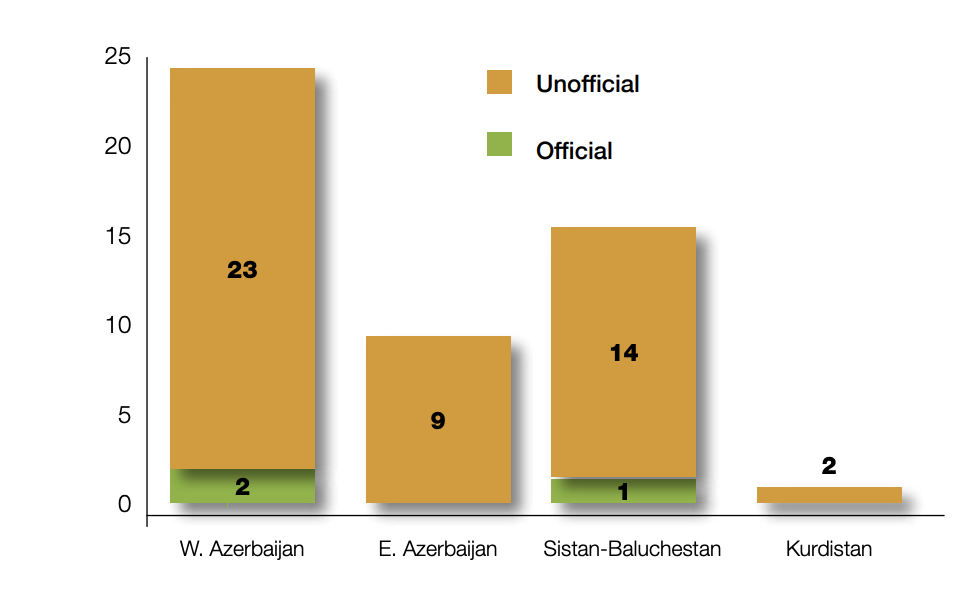

As in the last four years, most of the executions conducted in the ethnic regions of Iran in 2018 were not announced by official Iranian media. Specifically, 27 of the 50 executions IHR has managed to confirm in the provinces of East and West Azerbaijan, Kurdistan and Baluchestan, were not announced by official Iranian sources.

On the other hand, the absolute majority of all executions for political affiliation belong to the ethnic groups, particularly the Kurds (see the section about Moharebeh of the annual report 2018). An overview of the IHR reports between 2010 and 2018 shows that among the 118 people who have been executed for affiliation with banned political and militant groups, there were 65 Kurds (55%), 29 Baluchis (25%) and 15 Arabs (13%). It is important to notice that most of those executed among the ethnic groups were Sunni Muslims.

There are several reasons for the overrepresentation of ethnic groups among those executed. more opposition among people against the authorities leading to increased need of the authorities to use violence and create fear, presence of militant groups in these areas making it easier for the authorities to issue death sentences under the pretext of fighting terrorism, there is less visibility from the media and rights groups on the situation in certain ethnic regions. Besides poverty, poor socio-economic situation and the lawlessness and arbitrariness present in the Iranian Judiciary are even more serious in the ethnic regions.

In 2018, IHR received reports about possible execution of several Ahwazi Arab prisoners in the prison of Ahwaz. Further investigations confirmed that at least four prisoners were killed, but could not confirm whether these prisoners were executed or were killed under torture. Therefore, these four prisoners have not been included in the present report.[14]

Foreign citizens

In 2018, IHR reported about the executions of 16 foreign citizens. Most of them were Afghan citizens. The actual number is higher than reported here. Following protests by the Afghan civil society and some parliamentarians in 2012-2013, Iranian authorities often don’t announce the execution of Afghans. The same is probably true for other foreign citizens as the issue can raise international sensitivity. In 2016, three Turkish citizens were executed for drug-related charges. None of the executions were announced and despite knowing about the cases, the Turkish government didn’t show any public reactions to the executions. It is not known to what extent the death row foreign citizens in Iran receive consular support from their respective authorities.

Some facts about the foreign citizens who were executed in 2018 in Iran:

16 executions were reported

14 Afghan citizens were among the reported executions

1 Pakistani citizen executed

1 Iraqi citizen was among those executed

All reported executions were based on murder charges

According to IHR’s estimates, the number of foreign citizens, especially Afghans and Pakistanis executed are much higher than reported here. IHR is investigating the number of foreign citizens on the death row in Iran. This issue will be addressed further in a future report.