Qisas/Murder Executions and Forgiveness in 2022

As murder is specifically punished under qisas laws, the IPC does not explicitly state that convicted murderers are subject to the death penalty but rather to qisas, or “retribution-in-kind”. The law effectively puts the responsibility for executions for murder in the hands of the victim’s family or next of kin. Qisas death sentences are also imposed for juvenile offenders as, according to Sharia, the age of criminal responsibility for girls is 9 and for boys 15 lunar years. Furthermore, the death penalty is generally subject to discriminatory application based on gender, ethnicity and religion.

In addition to the inequality of citizens before the law, there are countless reports of violations of due process in qisas cases. Examples include the use of torture to extract confessions and summary trials without sufficient time to conduct independent investigation of the evidence and ineffective counsel.

Murder charges were the most common charge and qisas executions accounted for the most common execution category in 2022.

Facts about the qisas executions in 2022

- 288 executions were carried out for murder charges based on qisas laws (183 in 2021 and 211 in 2020)

- This is the highest number of annual qisas executions since 2010

- 46 qisas executions were announced by official sources (16%)

- 66 qisas executions were carried out in one prison (Rajai Shahr Prison)

- 3 juvenile offenders were executed (under 18 years of age at the time of offence)

- 13 of those executed for murder charges were women (none were announced by the authorities)

Executed for murder charges in 2022

The 288 qisas executions in 2022 include a variety of cases, the majority of which involve defendants being denied their rights to due process and a fair trial. The execution of juveniles and women can be found in “Execution Categories” on page 76.

Behzad Tahmtan: execution exposed wrongful execution

When cousins Behzad and Yousef Tahmtan were arrested, another prisoner called Babak Rezaei had already been mistakenly executed for murders committed by Behzad. The cousins were sentenced to qisas for murder and moharebeh through armed robbery. Babak Rezaei’s wrongful execution was not exposed until their execution on February 7.

Golmohammad (surname unknown): qisas requested by judiciary

Golmohammad was an Afghan national who was arrested for murder in April 2013. According to the police report, he had stabbed the victim who was his friend in a rage after discovering he was sexually abusing his young daughter. In the investigative phase of Golmohammad’s case, authorities were unable to find the victim’s family, leaving him in limbo until the Deputy Head of Judiciary requested qisas for him. He was sentenced to qisas six years after arrest by Branch One of the Alborz Criminal Court and executed on April 2 in Karaj Penitentiary. He was the only person executed during Ramadan.

Iman Sabzikar: First public execution in 2 years

Iman Sabzikar (Jonaghi) was a 28-year-old construction worker who was arrested for the murder of a policeman along with his brother Amin. According to his lawyer, he was denied access to his client. Severely tortured with broken limbs, jaw and teeth, Iman was taken to the scene of the crime and publicly tortured and humiliated by amongst others, the victim’s young son. On February 2, he was sentenced to death for qisas and the sentence was upheld by Branch 9 of the Supreme Court on July 12. Hearing news of the sentence, his brother Amin committed suicide in custody. Just six months after arrest, Iman was publicly executed on July 23.

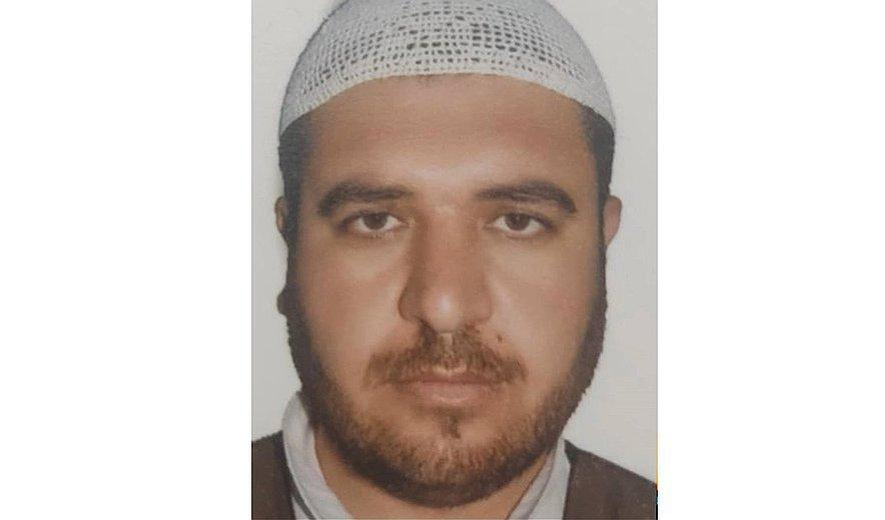

Sarajolhagh Sedighi: Pakistani Sunni cleric

Sarajolhagh Sedighi was a 45-year-old Pakistani Sunni cleric from the Baluch region of Pakistan who was arrested in 2017. He was sentenced to qisas for “participation in murder.” Sarajolhagh was transferred from Pirbano Prison to Shiraz Central for his execution which took place on July 24. His body was transferred back to Pakistan.

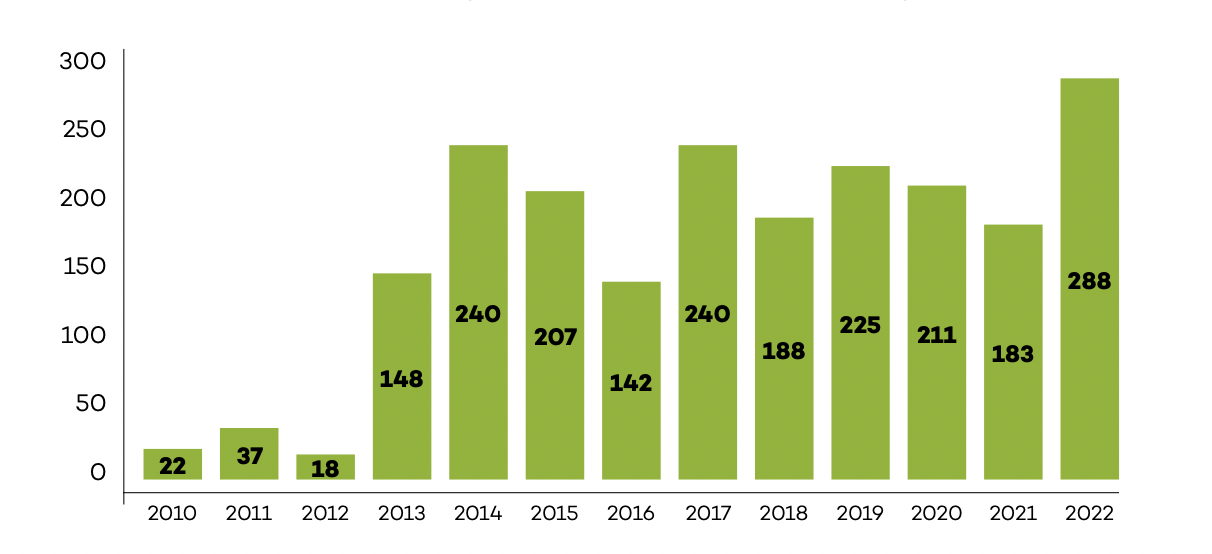

Qisas executions since 2010

According to data gathered by Iran Human Rights, at least 2,149 qisas executions were carried out between 2010 and 2022. The diagram below shows the trend of qisas executions during this period.

The number of qisas executions, which was relatively low between 2010 and 2012, increased dramatically in 2013 and has remained at a high level since. This coincides with growing international criticism of Iran’s drug-related executions. In 2022, at least 288 people were subjected to qisas executions.

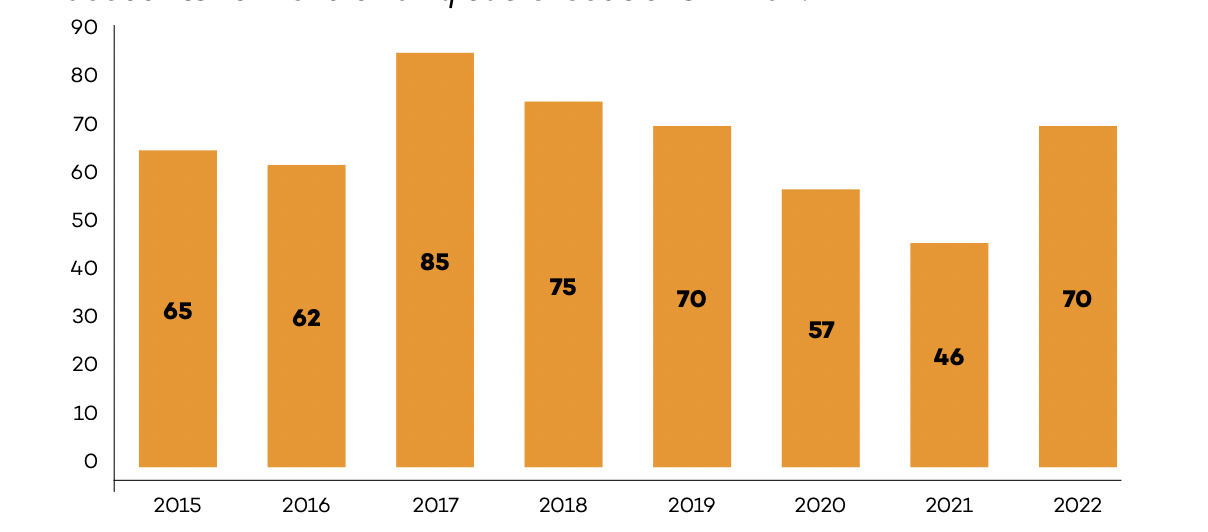

Rajai Shahr Prison: the qisas capital

The detailed geographical distribution of qisas executions will be provided under the “Forgiveness Movement” section of this report. However, reports in the last seven years demonstrate that each year, a significant portion of all qisas executions were carried out in one single prison in the Alborz/Tehran area. In addition, Rajai Shahr Prison (previously known as Gohardasht Prison) has been the site of the execution of many political prisoners, particularly those belonging to banned Kurdish political parties. In 2022, at least 66 qisas sentences were carried out in Rajai Shahr prison which accounts for 23% of all qisas executions in Iran.

The diagram above shows the number of implemented qisas death sentences in Alborz/Tehran prisons since 2015. 66 out of 70 qisas executions in Alborz province took place in Rajai Shahr Prison.

Blood money (diya) or forgiveness instead of death penalty in qisas cases

According to the IPC, murder is punished by qisas, where the victim’s next of kin can demand a retribution death sentence. But they can also demand diya (blood money) instead of retribution or can simply grant forgiveness. The Head of Judiciary sets an annual indicative amount for diya based on inflation and other considerations, but the victim’s family can choose their own amount. They can demand a lower or higher amount than the judiciary’s indicative number but crucially, no upper limit is set. This year’s diya, which was determined in March 2023, was set at 900 million tomans (€18,000) for a Muslim man and 450 million tomans for a Muslim woman.

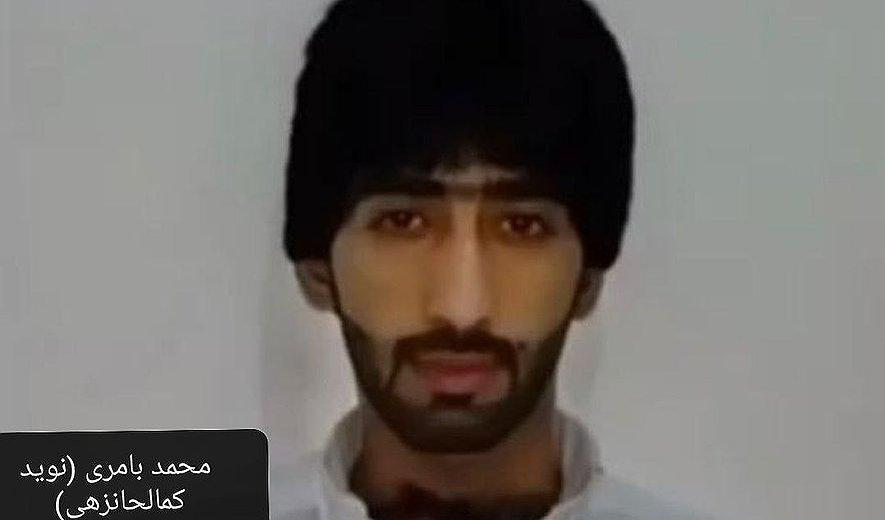

The amount set by families is usually higher than the indicative amount and even the indicative amount is higher than most families can afford. These are just two of the people who were executed because they could not afford diya:

Mohammad Bameri (photo), a Baluch man sentenced to qisas, was executed in Iranshahr Prison on 14 May 2022 after failing to pay the 1 billion tomans (€33k) diya demanded by the victims’ family.

Mehrab Salehi was executed on 15 May 2022 in Yazd Central Prison after failing to pay the 1.5 billion tomans (€50k) diya demanded by the victim’s family.

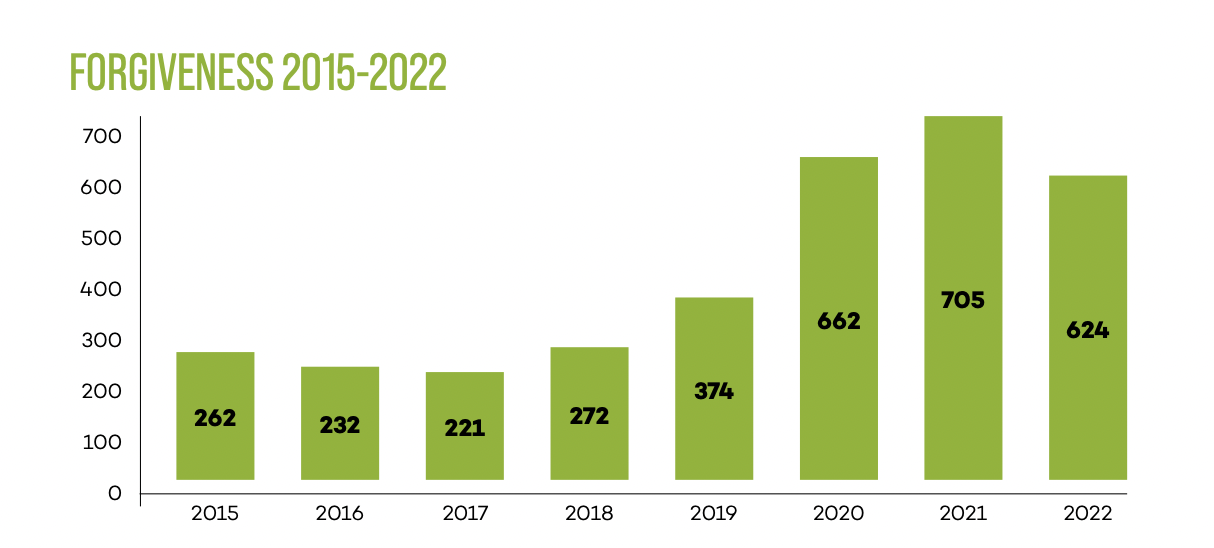

Iran Human Rights has collected forgiveness reports since 2015. According to the reports gathered in the past eight years, the families of murder victims who chose forgiveness or diya for murder convicts outnumber those who chose the death penalty.

For the sake of simplicity, we will use the term forgiveness in the following section, regardless of whether there has been a demand for diya or not.

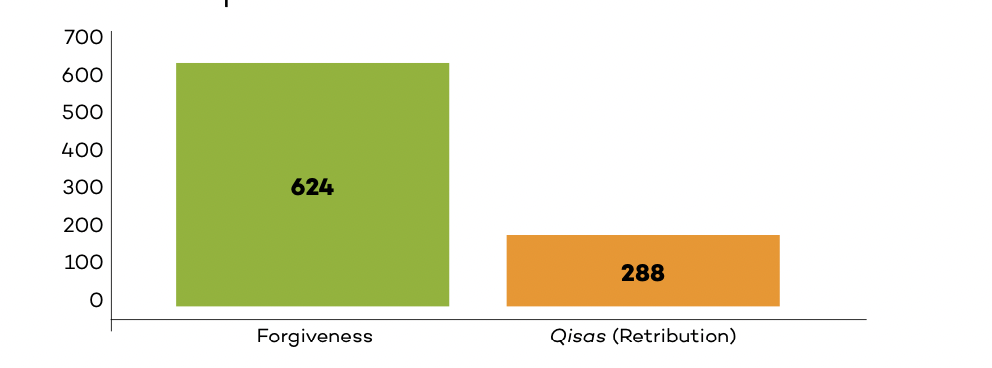

As for the execution numbers, not all forgiveness cases are reported by the Iranian media. Based on reports by the Iranian media and, to a lesser extent, through its own network inside Iran, Iran Human Rights has identified 624 forgiveness cases in 2022, compared to 705 cases in 2021, 662 cases in 2020, 374 in 2019 and 272 in 2018.

As in the previous five years, the forgiveness cases outnumbered those of implemented qisas executions in 2022. The actual numbers for both forgiveness and qisas death sentences are believed to be higher. Reports indicate that the number of forgiveness cases might be several folds higher than the numbers presented in this report.

The increasing trend of forgiveness in Iran correlates with a survey conducted for Iran Human Rights and World Coalition Against the Death Penalty (WCADP) in September 2020, which found that the majority of people prefer alternative punishments to the qisas death penalty for murder victims. Iranian authorities assert that qisas is the right of the plaintiff (the victim’s family/next of kin) and that most qisas executions take place upon the plaintiff’s request. However, when questioned about their preferred punishment if an immediate family member was murdered, only 21.5% of respondents chose qisas, while more than 50% preferred alternative punishments such as imprisonment.

A comparison of the number of implemented qisas death sentences and forgiveness cases in 2022

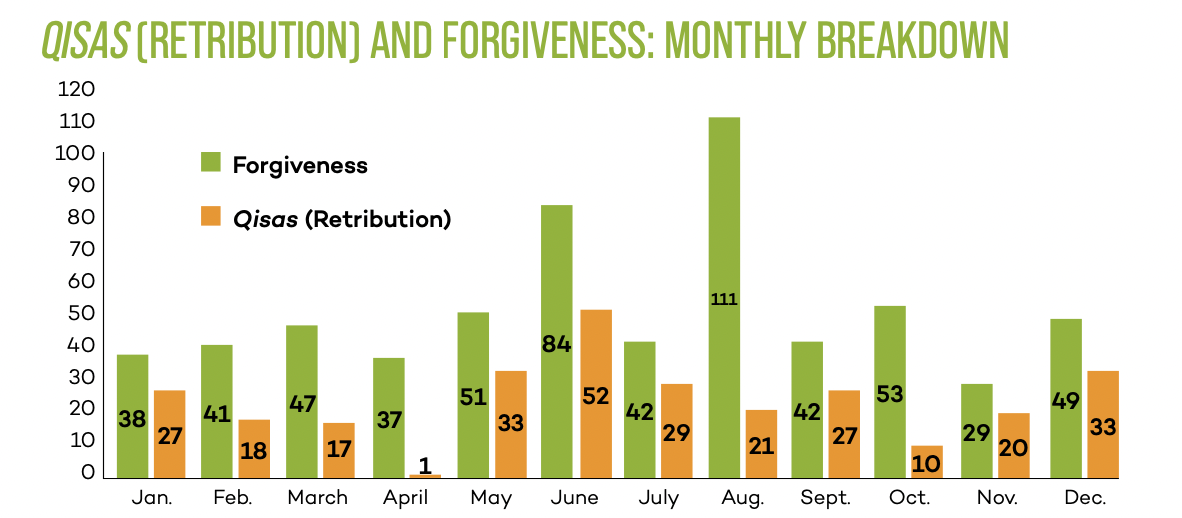

The diagram above shows the monthly breakdown of implemented qisas death sentences compared to forgiveness cases. Forgiveness cases outnumber those of qisas executions throughout the year.

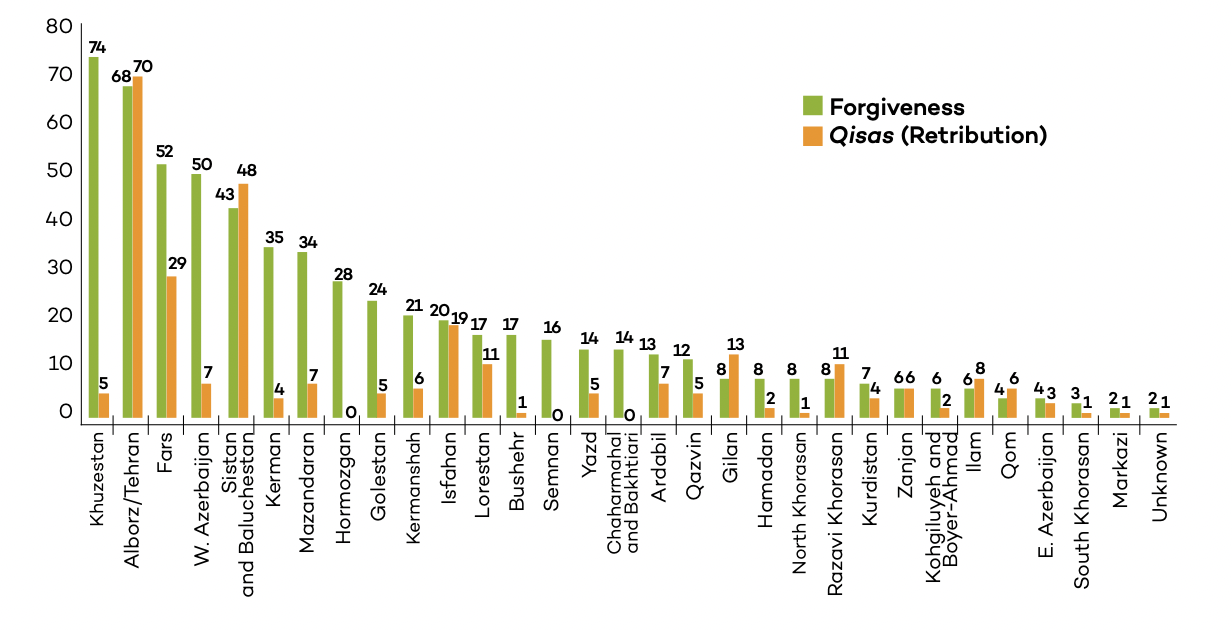

Qisas and forgiveness: geographic distribution

In 2022, Iran Human Rights recorded forgiveness cases in all 31 provinces in Iran. In comparison, qisas death sentences were reported in 28 of the provinces. In 20 provinces, the number of forgiveness cases were higher than qisas executions.

The number of qisas executions were higher than forgiveness in only six provinces, while the forgiveness numbers were higher than qisas executions in the rest of the provinces except one where they were equal. The number of forgiveness cases in Khuzestan was more than 14 times higher than the qisas numbers.