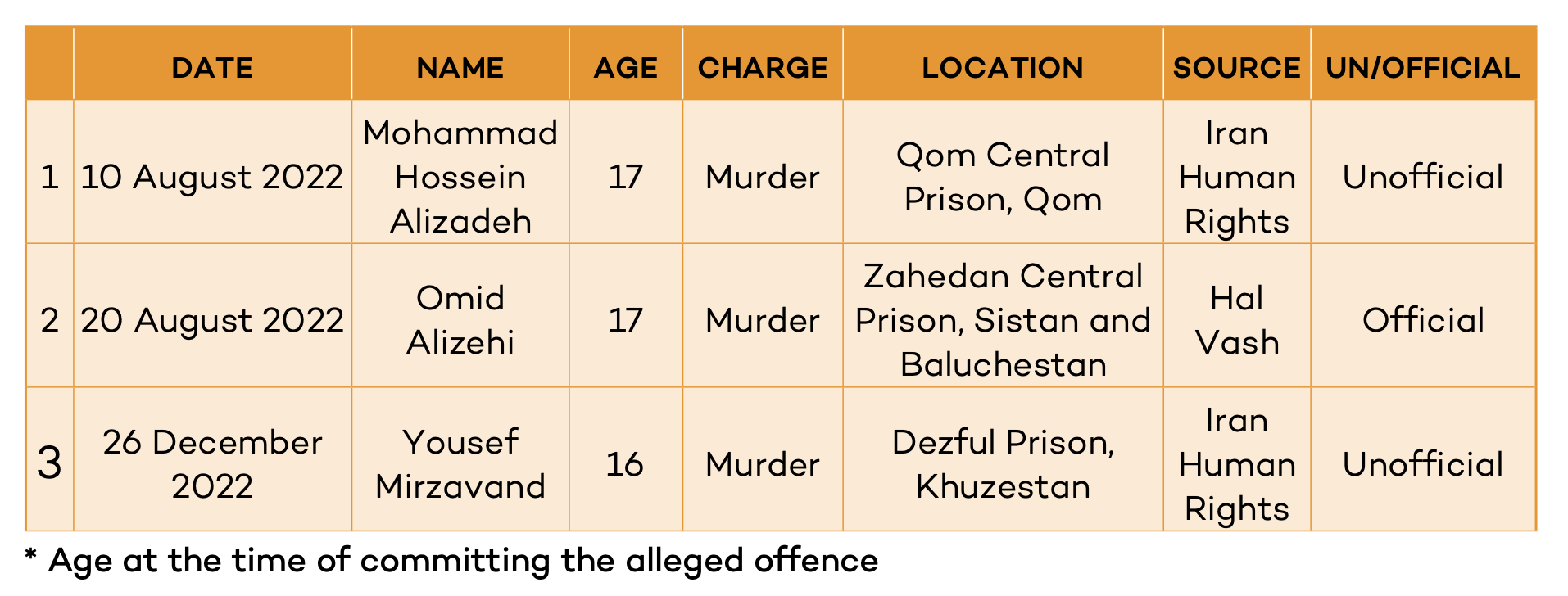

Juvenile Offender Executions in 2022

This is an extract from the 2022 Annual Report on the Death Penalty in Iran.

Juvenile executions: Trends and legislative reforms

Iran is one of the last remaining countries to sentence juvenile offenders to death and executes more juvenile offenders than any other country in the world. In violation of the International Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which Iran has ratified, Iranian authorities executed at least 3 juvenile offenders in 2022. According to Iran Human Rights' reports, at least 68 juvenile offenders were executed between 2010 and 2022 in Iran.[1] According to UN experts, there are currently at least 85 juveniles on death row in Iranian prisons.[2] However, the actual number is likely to be significantly higher as there is no information about juvenile offenders in many Iranian prisons.

The international pressure on Iran on this matter increased during the 2000-2010 decade. As a consequence of the criticism from the international community and domestic civil society, Iran made changes regarding juvenile offenders in the 2013 Islamic Penal Code (IPC). However, these changes have not led to a decrease in the number of juvenile executions. The 2013 IPC explicitly defines the “age of criminal responsibility” for children as the age of maturity under Sharia law, meaning that girls over 9 lunar years of age and boys over 15 lunar years of age are eligible for execution if convicted of “crimes against God” (such as apostasy) or “retribution crimes” (such as murder). Article 91 of the IPC states that juvenile offenders under the age of 18 who commit hudud or qisas offences may not be sentenced to death if the judge determines the offender lacked “adequate mental maturity and the ability to reason” based on forensic evidence.[3] The article allows judges to assess a juvenile offender’s mental maturity at the time of the offence and, potentially, to impose an alternative punishment to the death penalty on the basis of the outcome. In 2014, Iran’s Supreme Court confirmed that all juvenile offenders on death row could apply for retrial.

However, Article 91 is vaguely worded and inconsistently and arbitrarily applied. Between 2016-2022, Iran Human Rights identified 21 cases, where the death sentences of juvenile offenders were commuted based on Article 91. No Article 91 commuted sentences were reported or recorded in 2022. In the same period, according to Iran Human Rights' reports, at least 29 juvenile offenders were executed and several remain at risk of execution. It seems that Article 91 has not led to a decrease in the number of juvenile executions. The Iranian authorities must change the law, unconditionally removing all death sentences for all offences committed under 18 years of age.

According to the report of the UN Secretary-General on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran published in August 2021 at the 76th session of the UN General Assembly: “While article 91 of the Penal Code gives judges the discretion to exempt children from the death penalty, the continued imposition of death sentences for child offenders shows that that article has failed to have a significant impact.” He further stated: “the application of the death penalty on child offenders calls for a revision of the Penal Code to prohibit the imposition of the death penalty on individuals who were under 18 years of age at the time of the alleged crime, as well as the abolition of the death penalty.”[4]

In his October 2022 report to the 77th session of the UN General Assembly, he called on Iran’s government to “prohibit the execution of child offenders in all circumstances and to commute their sentences.”[5]

International human rights mechanisms have also repeatedly called on Iran to put an end to the execution of juvenile offenders. When Michelle Bachelet, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, criticised the Islamic Republic’s use of the death penalty in June 2021, stating that “over 80 child offenders are on death row,” it was dismissed by Islamic Republic officials. Deputy for International Affairs at Iran's High Council for Human Rights told AFP that the Islamic Republic only does that “three to four times a year” and that such uses of the death penalty “are not a symbol of violations of human rights.”[6] He also called the criticism “unfair.”[7] Stating that 85 juvenile offenders were on death row in Iran, a resolution passed in the European Parliament in February 2022 called on Iran to “urgently amend Article 91 of the Islamic Penal Code of Iran to explicitly prohibit the use of the death penalty for crimes committed by persons below 18 years of age, in all circumstances and without any discretion for judges to impose the death penalty or life imprisonment without the possibility of release.”[8]

In his 2022 annual report, Javaid Rehman, the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran, called on the Islamic Republic to “Urgently amend legislation to prohibit the execution of persons who committed a crime while under the age of 18 years, and urgently amend legislation to commute all death sentences for child offenders on death row.”[9]

Facts about juvenile executions in 2022:

- At least 3 juvenile offenders were executed

- All were boys charged with murder and sentenced to qisas

- 2 of the juvenile offenders executed, had committed murder in self defence

- Reports on the execution of 3 other juvenile offenders were not included in this report due to lack of sufficient documentation

Juvenile offenders executed in 2022

Mohammad Hossein Alizadeh: Unintentional murder against group attack

Mohammad Hossein Alizadeh was an Afghan national and 17 years old at the time of arrest. He had unintentionally committed murder when went to defend his cousin against a street group attack in 2016. He was arrested and sentenced to qisas for murder and executed aged 24 in Qom Central Prison on August 10.[10]

Omid Alizehi: Court ruled murder to have been unintentional

Omid Alizehi was Baluch and born on 22 July 2000 and arrested in December 2017/January 2018 (Dey 1396) when he was 17 years old, for an alleged murder committed during a street fight. According to a source close to his family, Omid was held in a juvenile correctional centre for the first two years before being transferred to the juvenile ward of Zahedan Central Prison. He was acquitted of murder at trial, with the murder caused in a street fight ruled to have been unintentional. However, Omid’s family were unable to afford a lawyer to pursue his case. According to sources, the victim’s family had the money to spend on changing his sentence. He was executed along with four other Baluch prisoners in Zahedan Central Prison on August 20.[11]

Yousef Mirzavand: took the rap for real culprit

Yousef Mirzavand was 16 when he was arrested for charges of “initiating an armed robbery, carrying hunting weapons without a licence, committing intentional assault with a weapon, murder, being accessory to murder and conspiracy to escape trial” and sentenced to death. According to his family, Yousef had taken the rap for the person who had committed the murder. He was 22 years old when he was executed in Dezful Prison on December 26.[12]

LIST OF JUVENILE OFFENDERS EXECUTED IN 2022

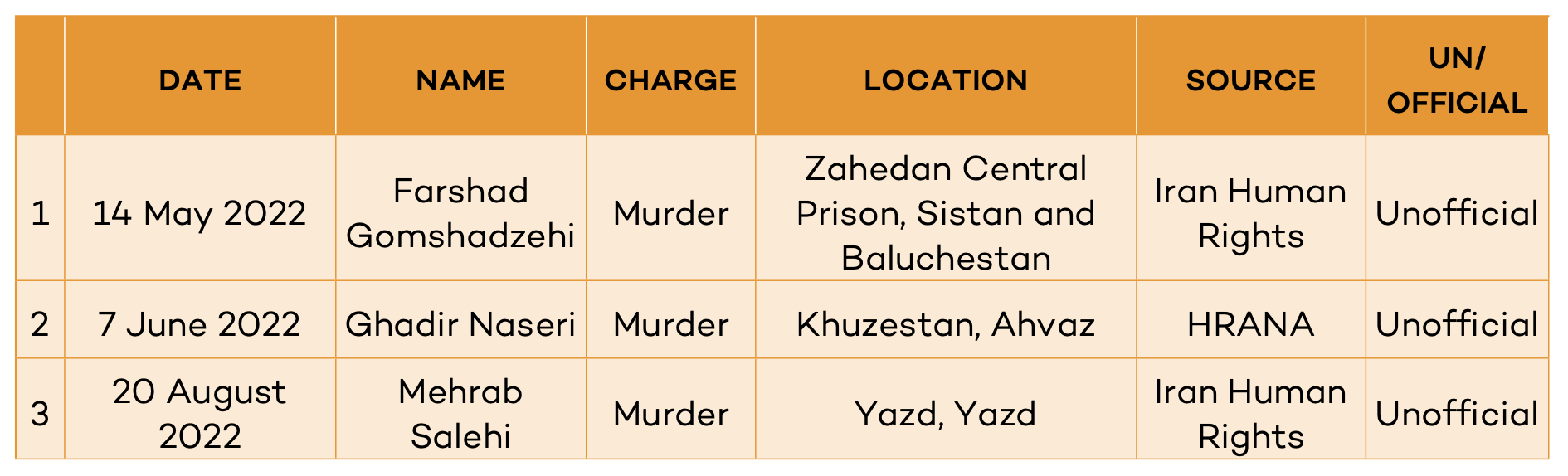

LIST OF POSSIBLE JUVENILE OFFENDERS EXECUTED IN 2022

[1] Iran Human Rights Execution Counter: https://iranhr.net/en/

[2] https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=27861&LangID=E

[3] https://undocs.org/A/68/377. See also Iran Penal Code (2013), Art. 91

[4] https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N21/216/25/PDF/N2121625.pdf?OpenElement

[5] https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N22/632/51/PDF/N2263251.pdf?OpenElement

[6] https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20210630-iran-says-executing-child-offenders-not-a-rights-violation

[7] https://iranhr.net/en/articles/4786/

[8] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0050_EN.html

[9] https://undocs.org/A/HRC/49/75

[10] https://iranhr.net/en/articles/5401/