Executions for Drug-related Charges in 2023

This is an extract from the 2023 Annual Report on the Death Penalty in Iran. To read the full report, please click here.

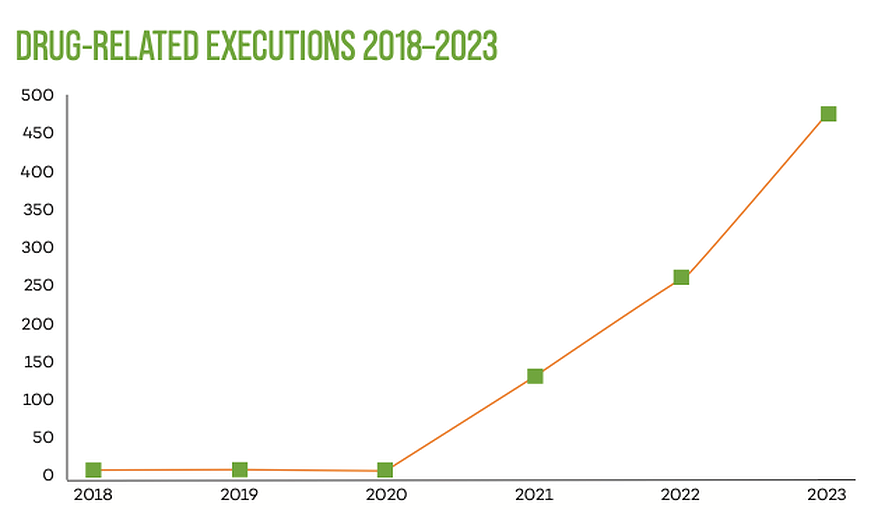

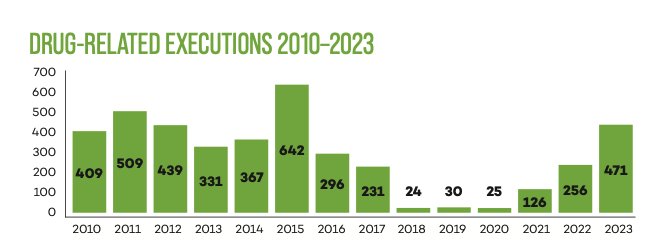

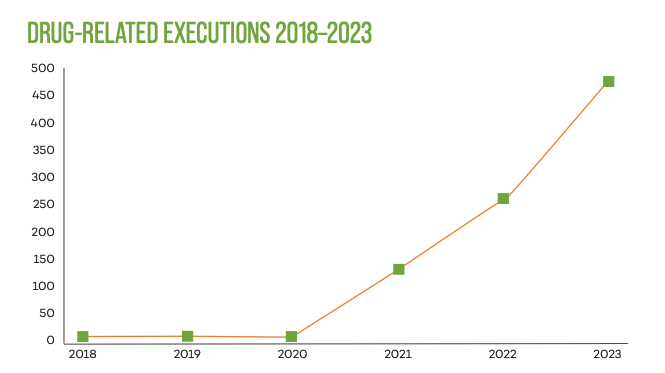

Drug executions have been steadily rising since 2021. Those executed for drug-related charges are amongst the most voiceless victims of the death penalty in Iran. Along with security charges, drug-related charges fall under the jurisdiction of the Revolutionary Courts which, as above mentioned, systematically deny defendants their right to due process and a fair trial. According to reports gathered by Iran Human Rights, at least 471 people were executed for drug-related offences in 2023.

Facts about drug-related executions in 2023

- At least 471 people were executed, an 84% rise compared to 2022 (256) and about 18 times the average of drug-related executions in 2018-2020)

- Only 25 drug-related executions were announced by official sources

- Executions took place in 26 different provinces

- Baluch minorities, who make up 2-6% of Iran’s population, are overrepresented with 138 executions (31%) compared to 47% (121) in 2022 and 43% (55) in 2021.

- 3 women were executed for drug-related offences

According to Iran Human Rights reports, an annual average of at least 403 people were executed for drug-related offences between 2010 and 2017. The diagram above shows the reduction in the number of drug-related executions observed in the three years following the enforcement of the Amendment to the Anti-Narcotics Law at the end of 2017.

Drug-related executions increased by eighteen-fold in 2023 compared to the average number of drug executions between 2018 and 2020.

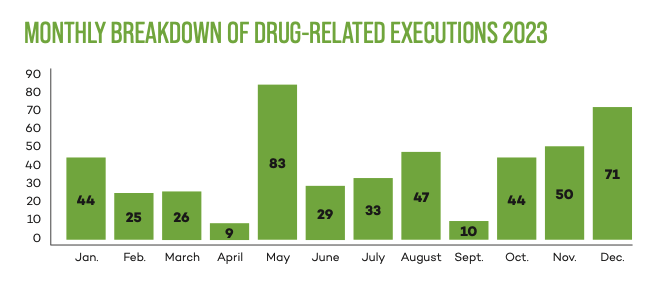

Executions for drug-related offences were carried every month of the year. The peak was in May, following the Nowruz and Ramadan holidays, when fewer executions are carried out.

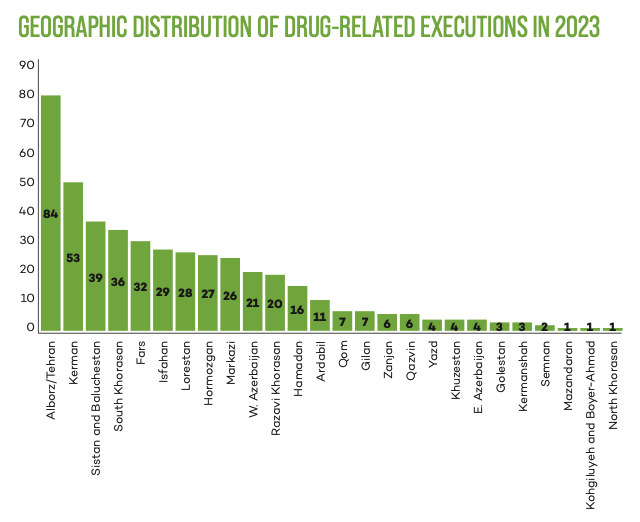

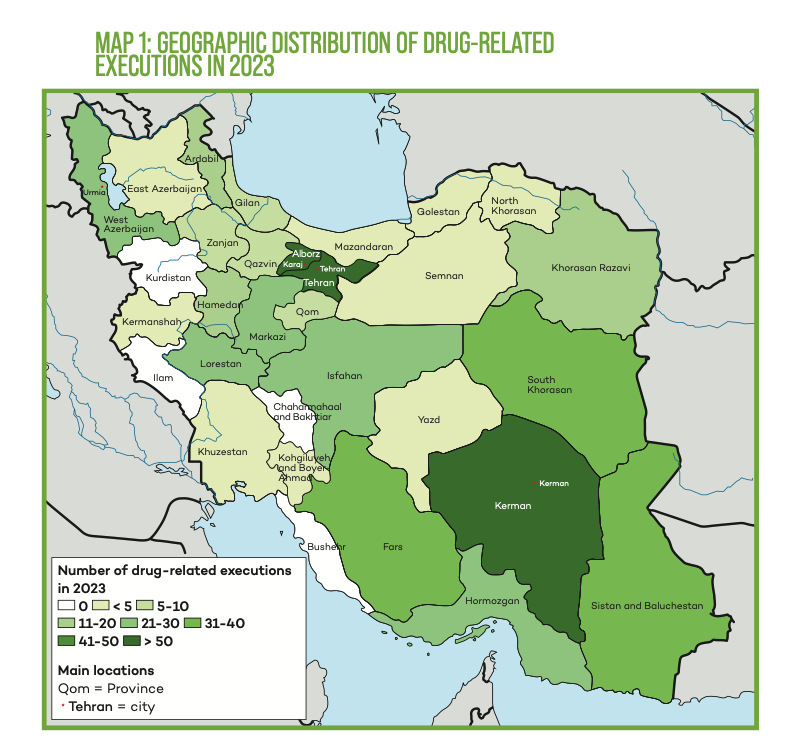

In 2023, drug-related executions were carried out across 26 difference provinces, an increase from 21 in 2022 and 15 in 2021. The highest number of drug-related executions were carried out in Alborz/Tehran provinces.

In 2023, Iran Human Rights reported drug-related executions in 26 provinces, compared to 21 in 2022, 15 in 2021, 12 in 2019 and 2020 and 7 provinces in 2018.

Executed for drug-related charges

The following are a very small sample of the people executed for drug-related charges in 2023.

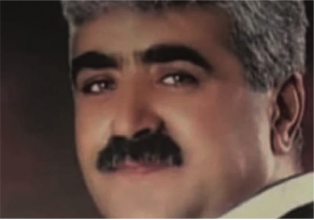

Mohammad Rasoul Shehbakhsh

Mohammad Rasoul Shehbakhsh (Notizehi) was a 44-year-old Baluch man arrested for drug charges after being shot 8 times in the abdomen and legs. He was sentenced to death by the Kerman Revolutionary Court without a lawyer present. Despite his sentence being overturned by the Supreme Court four times, he was told by Judge Ghorbani at Branch 1 of the Kerman Revolutionary Court that he “had to be executed.” Mohammad was executed in Kerman Central Prison on 8 January 2023.[1]

Nazir Sorkhkaman

Nazir Sorkhkaman was a 28-year-old undocumented Baluch man from the village of Milak in Zabol. He was arrested for drug-related charges and sentenced to death by the Roudan Revolutionary Court. His execution was carried out in Roudan Prison on 9 January 2023 without notification, depriving him of the right to say goodbye to his family.[2]

Ehsan Dehghanipour

At 25, Ehsan Dehghanipour’s father was executed for drug-related charges in Khorramabad. Three months later, Ehsan himself was arrested for the same charges. He was sentenced to death by the Revolutionary Court and spent 10 years on death row before being executed aged 35 in Boroujerd Prison on 29 August 2023.[3]

Saeed and Esmail Alizehi

Esmail Alizehi, 29, and his brother, Saeed Alizehi, 25, were arrested at the Zabol border region in 2021 without any drugs ever being found. They vehemently denied the charges in court, but were ignored by the judge who sentenced them to death without any evidence. Their executions were carried out in Zahedan Central Prison on 4 November 2023 without prior notification, denying them the right to say goodbye to their family who lost two sons that day.[4]

Hossein Mohammadi

Twelve years prior to his execution, Hossein Mohammadi, a Kurdish father, was organising his son’s wedding and needed to go to Tehran to bring back his sister. His neighbour offered him a lift and said “you can help me on the way there.” Unbeknown to Hossein, his neighbour was carrying drugs for which they were arrested. Hossein Mohammadi was executed in Rasht Central Prison on 12 October 2023. He was the third of his relatives to be executed. One of his relatives, Esmail Mohamad was executed for membership in the Komala party in 2005.[5]

Dramatic increase in drug-related executions: The UNODC maintains silence on executions and signs new cooperation agreement with the Islamic Republic of Iran

The last Amendment to Iran’s Anti-Narcotics Law came into force on 14 November 2017, leading to a significant drop in the number of drug-related executions, from an annual average of 403 to an average of 26 executions in the proceeding three years. The number of commuted death sentences as a result of this Amendment could be as high as 6,000, according to Islamic Republic lawmaker Hassan Norouzi.[6] However, this trend was reversed in 2021, and the number of drug-related executions have dramatically increased since (see diagram on page XX). The number of drug-related executions in 2023 was more than 18 times higher than the number in 2020.

Iranian authorities introduced the 2017 Amendment to the Anti-Narcotics Law mainly due to international pressure. Crucially, European states funding UNODC projects to combat illegal drugs in Iran were unwilling to fund any further projects due to the high number of drug-related executions.[7]

Both in the 2021 and 2022 Annual Reports on the Death Penalty, Iran Human Rights and ECPM have expressed grave concern about the alarming rise in the number of drug-related executions and called on the UNODC to react.[8] However, not only has the UNODC not acknowledged this dramatic rise, in March 2023, the organisation signed a new agreement to enhance its cooperation with the Islamic Republic of Iran.[9] This cooperation includes a sub-program on “Border management and illicit trafficking”, which aims to provide “technical training and support designed to upgrade and enhance the capacities and technical knowledge of law enforcement and Anti-Narcotic Police (ANP).[10] Such support can lead to more arrests, convictions and executions.

Moreover, Iranian authorities use the cooperation with the UNODC as an argument to justify the execution of alleged drug offenders.[11] UNODC’s silence on the execution of hundreds annually, in addition to its support of Iran’s law enforcement and providing political legitimacy for the executions, makes it complicit in the executions.

Drug executions: Costless victims of the death penalty for political repression

Iranian authorities use the death penalty as a tool of political repression. Iran Human Rights’ analysis has shown that there is a meaningful correlation between the number of executions and political events.[12] Following the outbreak of the “Woman, Life, Freedom” nationwide protests, officials publicly threatened protesters with the death penalty. However, the strong international backlash made the execution of protesters politically costly for the Islamic Republic. Since then, we have observed a great increase in the number of drug-related executions, despite the Islamic Republic’s own repeated admission that the death penalty does not deter drug crimes.[13]

Thus, the authorities’ need to instil fear in society in order to prevent further protests is the most likely reason for the sharp increase in the number of drug-related executions. Drug offenders are predominantly from the most marginalised groups in society, and ethnic minorities -the Baluch in particular- are grossly overrepresented among those executed. This, together with the international community’s silence, and in part UNODC’s cooperation, makes the political cost of their execution very low. All drug-related offences are processed by the Revolutionary Courts. Reports collected by Iran Human Rights demonstrate that those arrested for drug-related offences are systematically subjected to torture in the weeks following their arrest. They often do not have access to a lawyer while in detention, and by the time a lawyer gains access to their case, they have already “confessed” to the crime.[14] Revolutionary Court trials are also typically very short, with lawyers often not even given a chance to present a defence for their clients. As such, the authorities can accuse anyone with drug-related charges and sentence them to death anytime they desire to do so.

[1] https://iranhr.net/en/articles/5692/

[2] https://iranhr.net/en/articles/5693/

[3] https://iranhr.net/en/articles/6179/

[4] https://iranhr.net/en/articles/6289/

[5] https://iranhr.net/en/articles/6234/

[6] https://www.rokna.net/بخش-اخبار-سیاسی-74/957563-نوروزی-رئیسی-با-محافظ-به-پرند-رفت-نوری-قزلجه-ازاعدام-هزار-جوان-به-جرم-مواد-مخدر-جلوگیری-کردیم

[7] https://www.rte.ie/news/2013/1108/485366-ireland-anti-drug-iran/

[8] https://iranhr.net/media/files/Rapport_iran_2022_PirQr2V.pdf

[9] https://www.unodc.org/islamicrepublicofiran/en/unodc-and-iran-enhance-cooperation-in-the-field-of-drugs-and-crime.html

[10] https://www.unodc.org/islamicrepublicofiran/border-management-and-illicit-trafficking.html

[11] https://www.mizanonline.ir/fa/news/4713713/نقش-مهم-ایران-در-مبارزه-با-قاچاق-مواد-مخدر-و-تروریسم-وقتی-که-غرب-حامی-قاچاقچیان-و-تروریست%E2%80%8Eها-می%E2%80%8Eشود

[12] https://iranhr.net/en/articles/982/

[13] https://iranhr.net/en/articles/2408/

[14] https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/12/16/iran-bid-end-drug-offence-executions