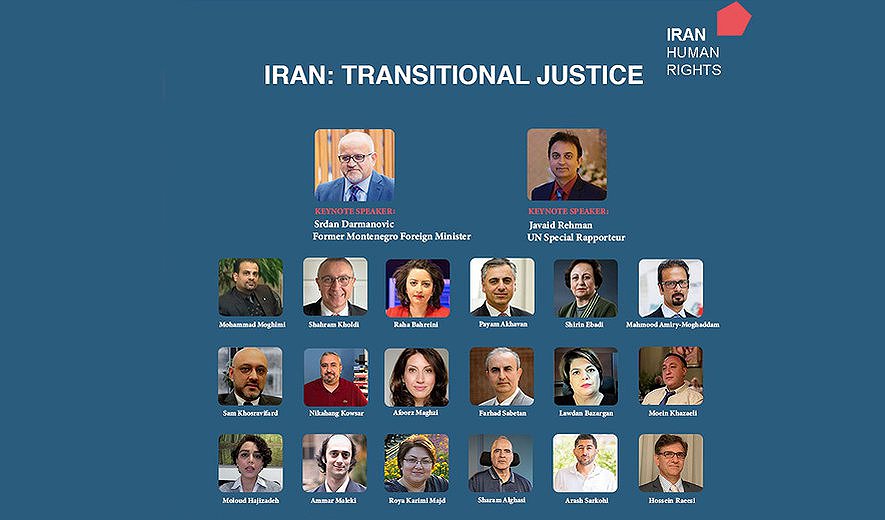

Conference Report: Iran's Path Forward and Transitional Justice

Iran Human Rights NGO (IHRNGO) hosted a conference titled ‘Iran: Transitional Justice’ on 1-2 September in Oslo, Norway. This was the third event in the series of conferences focused on transition from authoritarianism to democracy in Iran, which aims to create debate between citizens and experts on the challenges of the transition period, and in parallel, to propose solutions by examining different transition models which will guarantee the rights of all Iranians. In this year’s gathering, human rights experts from Iran and elsewhere discussed the legal, social and educational needs for a peaceful transition to democracy in Iran, mindful of the historical experiences of other nations in this quest.

Each of the panels in the conference focused on particular aspects of transitional justice, but they also highlighted intersectional and common themes and complexities, including an emphasis on the importance of revisiting historical realities of transitions not only to foresee potential threats and strengths, but also in order to maintain and preserve democratic structures post-transition. In this sense, the importance of various activities and mechanisms were highlighted including: raising awareness about the atrocities of the current regime; educating people on the nature and meaning of justice and the means of attaining it in a democratic society; improving media literacy and ability to identify mis-/dis-information; and training new lawyers and legal experts to uphold the rule of law. The speakers further drew attention to the adverse impact of life under authoritarian rule on public health, human and natural resources and emphasised the importance of policies aimed both at compensating lost resources and moving towards sustainable development. All of the experts present agreed on the importance of a comprehensive approach to justice, and the need for extensive cultural education for improving popular understanding of the notion and its various manifestations in socio-political life.

In addition to the specialised panels, the conference also included keynote speeches by Javaid Rehman (UN Special Rapporteur) and Srdan Darmanovic (Former Montenegro Foreign Minister). In his speech, Dermanovic noted that although rereading the experience of different countries such as the west Balkans offers important lessons for Iran, none of the European examples are able to offer a complete roadmap for the country. This stems from Iran’s unique circumstances in light of the religious ideology of the authoritarian system and the central rule of clerics in political power structures, which along with the 44-year reign of the regime, distinguishes it from modern experiences of transition in Europe.

What follows is a more detailed look at the content of the panel discussions in the conference.

The first panel focused on the notion of transitional justice itself, with contributions from Mahmood Amiry-Moghadam (Director of Iran Human Rights), Shirin Ebadi (Human Rights Lawyer and Nobel Peace Prize Laureate), and Payam Akhavan (International Human Rights Lawyer and former UN Prosecutor). Highlighting the human rights violations aiming to suppress the protests in the last year, Amiry-Moghadam emphasised the importance of preparations for transition and cooperation of political groups on the basis of human rights priorities. In the context of Iran, he noted justice included ‘making visible all the atrocities of the past 44 years, putting all the facilitators of said atrocities on trial, seeking justice for victims, and structural changes in the political and justice systems’, with the aim of preventing the repeat of these atrocities in the future. Ebadi focused her speech on the legal mechanisms of transitional justice and defined the notion as a set of legal and non-legal actions that facilitate progression from authoritarianism to a stable, democratic, and peaceful society with the ability for sustainable development and preventing the reemergence of authoritarianism in the future. As she noted, although transitional justice does not necessarily have to follow a change in the governing regime (as in the case of Columbia where these policies were enacted at a point of impasse for the regime), in the case of Iran, given the fundamental inconsistency of religious authoritarianism with transitional justice, pursuing justice is predicated on the overthrow of the political system. Some of the key tangible actions that could then be taken include the release of political prisoners; disbanding institutions responsible for human rights violations such as IRGC; creation of fact-finding commissions to pursue the truth of atrocities committed; compensatory programmes for survivors; and criminal charges against instigators of atrocities. Ebadi noted the importance of such mechanisms for returning peace to a wounded society and to prevent future unrest. Following her, Akhavan examined some of the moral and political questions related to transitional justice noting that in the course of Jina Uprising this notion has become a popular demand. Key among these questions were those of how justice can be served in a situation where institutions tasked with ensuring justice and the rule of law have themselves become agents and enablers of injustice; and how in progressing towards democracy trust in institutions can be returned to the society. In such circumstances, Akhavan argued for the need to focus on reinstating lost dignity and respect to the victims and efforts to regain civil rights and compensate their suffering, as well as pursuing broad social change. As he noted, social acceptance of the victims’ experiences as instances of injustice, and the acknowledgement that violations of human rights are made possible in part by the silence of those bearing witness to them are some of necessities to ensure such atrocities are not repeated.

In the second panel focused on legal frameworks and mechanisms in the transitional period, Raha Bahreini (Legal Expert and Researcher at Amnesty International) talked expansively about executive policies of transitional justice, in particular the workings of fact-finding commissions and criminal trials, and the distinguishing characteristics of the two processes. As Bahreini explained, while commissions are an occasion for understanding mechanisms of oppression and recording the pain and suffering of victims from their own perspectives, trials aim at investigating particular crimes and atrocities, and testimonies by the wounded act only as a piece of evidence in the criminal case. Shahram Kholdi (Professor of History and International Relations at University of Waterloo, CA) pointed to the potential threat of wide-spread revenge-seeking during transition period in Iran which could target anyone who has denied citizens their right and talked about the necessity and importance of establishing prosecutorial processes. According to Kholdi, the current judicial system in Iran is the result of a reversal in a process of modernisation which began following the Constitutional Revolution, and has seen the system decline in the course of the Islamic regime’s governance into an institution guaranteeing systematic injustice in the country. As such, a key part of establishing a new judiciary system is the education of new lawyers, judges, and other officers of the law. Focusing on the topic of judicial violence in the transition period, Mohammad Moghimi (Lawyer and Human Rights Law Expert) pointed to the important role a council of legal experts could play in democratising the process of transition, social healing, respect of human rights and the ultimate establishment of the rule of law. According to Moghimi, such a council could publish guidelines and principles that ought to frame political power, while maintaining independence, impartiality and disinterest regarding those in power. Moein Khazaeli (Legal expert and Human Rights Researcher) ended the roundtable discussion by emphasising the need to re-establish trust in government institutions in the transition period, especially the judicial system, and pointing to institutional reform as the key tool for doing so. As he proposed, institutional reform aims to reconstruct government institutions and transform them from oppressive and law-escaping entities into law-abiding ones in service of citizens’ rights.

In the environmental justice roundtable, Nikahang Kowsar (Environment and Water Analyst) focused on issues of drought and water shortages in Iran, noting the interrelation of social, economic and environmental justice. Revisiting the experience of war and unrest in Syria and the refugee crisis that followed, Kowsar proposed transitional justice itself would not be possible without just and proper management of water resources. Following Kowsar, Sam Khosravifard (Environment Expert and Analyst) spoke about potential harm to the environment during transition period and the unrests that precede and follow it, and with a look back at the experiences of other countries noted the importance of raising environmental literacy and encouraging citizen participation in drafting and implementing policies with an emphasis on sustainable development. According to Khosravifard, in the vulnerable environmental circumstances of Iran, worsened by the climate emergency, it is important to implement policies firmly based on scientific advances and methods in the stable post-transition time, in order to offer longterm environmental security. Hossein Raeesi (Human Rights Lawyer and Law professor at University of Ottawa, CA) then spoke about discrimination that results from the climate emergency, mismanagement and destruction of resources, drawing attention to the notion of climate justice. Complementing points raised by Khosravifard, Raeesi highlighted the importance of care and preventive plans against a situation in which following political transition, Iranians are left with a scorched-earth scenario unable to restore environmental health vitality.

The fourth panel focused on the economics of transitional justice. Arash Sarkohi (Human Rights Consultant in the German Parliament), with a historical look back at the German experience of economic justice after the World War II and later after the fall of the Berlin Wall, noted that in Iran, where corruption governs economic relations, justice will never be fully served. Yet, what is important and needed in transition away from these relations, are transparency, raising social awareness, and gaining acknowledgment of responsibility by institutions benefitting from this system. Shirin Ebadi revisited economic policies following the 1979 revolution which saw the seizure of assets held by those deemed to be officers and enablers of the past regime, to argue for the importance of executive and oversight institutions managing the national wealth during the transition period. According to her, proper management in this area would prevent the repeat of events in ’79 when much of the economic capital was lost as people attempted to save their personal wealth by moving it out of Iran, which is seen as one of the key drivers of economic hardship in the following years in the country. Farhad Sabetan (Economist and Economics Professor in California State University, USA) focused his time on delineating the interrelation of economic and social discrimination and oppression. Noting the experience of countries like Apartheid South Africa where racial discrimination also included and was worsened by economic discrimination and oppression, highlighted the importance of following economic policies in line with and facilitating the aims of economic justice.

The final panel in the conference was focused on countering false information in transition period. Shahram Alghasi (Professor of Sociology, Culture, and Communications) noted that since media have always been controlled by the levers of power in Iran, the process of change in access and use of media in the West has not happened in the country and instead, today the regime in Iran uses the online world and in particular social media platforms to advance its own aims and agenda. Among such uses, Alghasi pointed to different active users and groups on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter) and Instagram, which spread false information and news stories, including in the course of the 2022 uprising. Recognising Islamic Republic’s active use of such platforms rather than removing popular access to them, Alghasi advocated for improving media literacy among people, including the ability to distinguish true information and trustworthy resources from the false and misleading ones. Reemphasising the importance of correct information as a bedrock foundation of transition to democracy, Roya Karimi Majd (Journalist at RadioFarda) spoke about the need for continuous education, not only for citizens but also for journalists. According to her, people in Iran have been in a maze searching for correct information, as local media outlets in the country are not trusted and professional media are a rare sight inside and outside the country. In this context, despite the widespread prevalence of mis- and disinformation, social media platforms have become the number one source of news for Iranians with significant power to influence popular opinions. Ammar Maleki (Assistant professor of Political Science at Tilburg University and founder of Gaman research institute) offered an analysis of different forms of propaganda and lack of recognition of plurality, both in the Iranian regime as well as some opposition forces. Basing his talk on the findings of research conducted by Gaman institute, he enumerated different modes of definition and interpretation of data in propaganda materials - including exaggeration; warping and claiming ownership of the truth; and normalising atrocities. Moloud Hajizadeh (Journalist) drew attention to the erosion of truth in the course of Jina movement, and the adverse impacts it has had on the movement’s progress. She, too, emphasised the importance of creating institutions as a way of combatting the spread of false information. In a context where events happen at a high speed and remain unpredictable, the probability of derailing or eroding movements and instead creating hopelessness and despair in society increases considerably. Within such circumstances, Hajizadeh argued, the role of popular media in fact-checking and protecting public trust is more important than ever.